A Nurse Is Providing Education About Family Bonding to Parents Who Recently Adopted a Newborn

- Research commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

Barriers and enablers of health system adoption of kangaroo mother intendance: a systematic review of caregiver perspectives

BMC Pediatrics volume 17, Article number:35 (2017) Cite this article

Abstract

Groundwork

Despite improvements in child survival in the past iv decades, an estimated 6.three 1000000 children nether the age of five dice each twelvemonth, and more than than xl% of these deaths occur in the neonatal menstruum. Interventions to reduce neonatal mortality are needed. Kangaroo female parent care (KMC) is one such life-saving intervention; still it has not however been fully integrated into health systems effectually the world. Utilizing a conceptual framework for integration of targeted health interventions into wellness systems, nosotros hypothesize that caregivers play a critical part in the adoption, improvidence, and absorption of KMC. The objective of this inquiry was to identify barriers and enablers of implementation and scale up of KMC from caregivers' perspective.

Methods

We searched Pubmed, Embase, Spider web of Science, Scopus, and WHO regional databases using search terms 'kangaroo female parent care' or 'kangaroo care' or 'peel to pare care'. Studies published between Jan 1, 1960 and August xix, 2015 were included. To be eligible, published work had to exist based on primary data collection regarding barriers or enablers of KMC implementation from the family unit perspective. Abstracted information were linked to the conceptual framework using a deductive approach, and themes were identified within each of the 5 framework areas using Nvivo software.

Results

We identified a total of 2875 abstracts. After removing duplicates and ineligible studies, 98 were included in the analysis. The majority of publications were published inside the past 5 years, had a sample size less than 50, and recruited participants from health facilities. Approximately 1-3rd of the studies were conducted in the Americas, and 26.5% were conducted in Africa.

We identified iv themes surrounding the interaction betwixt families and the KMC intervention: buy in and bonding (i.e. benefits of KMC to mothers and infants and perceptions of bonding betwixt mother and infant), social support (i.e. assistance from other people to perform KMC), sufficient fourth dimension to perform KMC, and medical concerns about mother or newborn health. Furthermore, we identified barriers and enablers of KMC adoption by caregivers within the context of the health organisation regarding financing and service delivery. Embedded within the broad social context, barriers to KMC adoption past caregivers included adherence to traditional newborn practices, stigma surrounding having a preterm infant, and gender roles regarding childcare.

Conclusion

Efforts to calibration up and integrate KMC into health systems must reduce barriers in order to promote the uptake of the intervention past caregivers.

Background

Despite improvements in child survival in the past four decades, an estimated 6.3 million children under the age of v die each year, and more than xl% of these deaths occur in the neonatal period [1]. Complications related to preterm birth is the leading crusade of expiry amidst children under five [two]. Effective implementation, at scale, of evidence-based interventions to reduce complications of preterm birth and associated neonatal bloodshed is needed.

Kangaroo Female parent Intendance (KMC) is one such testify-based, life-saving intervention. There are four components of KMC including: 1) early on, continuous, and prolonged skin-to-skin contact betwixt infant and caregiver, 2) sectional breastfeeding, 3) early on discharge from hospital, and 4) adequate support for caregiver and infant at domicile [3, 4]. In add-on to providing thermal control, KMC is associated with a 36% reduced risk of neonatal mortality among low nascence weight newborns compared to conventional care, besides as a significantly reduced risk of sepsis, hypoglycemia, and hypothermia [5].

Despite the strong bear witness regarding the improved health outcomes among preterm or low birth weight infants receiving KMC, including a recent recommendation past the World Health Organization that KMC should be routine care for newborns weighing less than 2000 g [6], this intervention has never been fully integrated into health systems around the world. A previous systematic review identified barriers to health system adoption of KMC and noted that families play an important role in KMC adoption [seven]. Further, the review noted that family unit interactions with the wellness system were critical to KMC adoption. Caregivers (e.g. mothers, fathers, and families) are key implementers and beneficiaries of KMC. We explore the barriers and enablers of KMC implementation from the caregiver perspective in greater particular.

In society to empathize the office of families in the adoption, diffusion, and assimilation of KMC, we build on a conceptual framework for integration of targeted health interventions into health systems [7, 8]. This framework promotes analysis in five areas including: (one) definition of the problem; (2) definition and attributes, such equally the 'relative advantage' and 'complexity', of the intervention package; (3) the adoption system including key actors, their interest, values and the ability dynamics between them; (iv) health system characteristics; and (five) the wide context including demographic, economic, and cultural factors.

Using this framework, we analyzed how caregivers perceive the risks and benefits of the intervention, too equally their values and interests surrounding KMC. Specifically, we identified barriers and enablers of implementation and scale upwards of kangaroo mother care based on the first systematic review on KMC implementation and uptake from the caregiver perspective.

Methods

In order to identify research studies for this review, we searched Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, AIM, LILACS, IMEMR, IMSEAR, and WPRIM. Search terms included: 'kangaroo mother care,' or 'kangaroo care,' or 'skin to skin care'. Studies published between January 1, 1960 and August 19, 2015 were included. Nosotros as well reviewed the references of published systematic reviews, searched unpublished programmatic reports, and requested information from the Saving Newborn Lives Program at Save the Children. We excluded studies if they did not include human subjects and main information drove. To exist eligible for inclusion into the review, published work had to include information near barriers to or enablers of successful implementation of KMC from the family perspective based on the experience of caregivers and health providers who had implemented KMC.

Ii independent reviewers used a standardized data abstraction course to assess eligibility and abstract information from each article. If the case reviewers did not agree most the inclusion of a study, a third reviewer bankrupt the tie. Each eligible report was assessed for the potential take a chance of bias in five domains including: option bias, appropriateness of data collection, ceremoniousness of data analysis, generalizability, and consideration of ideals [9].

Through several iterations of manual annotation and indexing, 2 researchers coded themes, perspectives and experiences using NVivo software. Bathetic information were linked to the conceptual framework using a deductive approach, and themes were identified within each of the five framework areas. Narratives were constructed around each major theme, and we used quotes to summarize perspectives from each study. The major themes and narratives were used to develop matrices where we defined important concepts, the range and nature of each theme, and the human relationship between themes. We used this meta-synthesis arroyo based on our objective of understanding caregiver perception and our hope that the results can inform policy and enhance our understanding of how to implement this complex intervention inside health systems [10].

Results

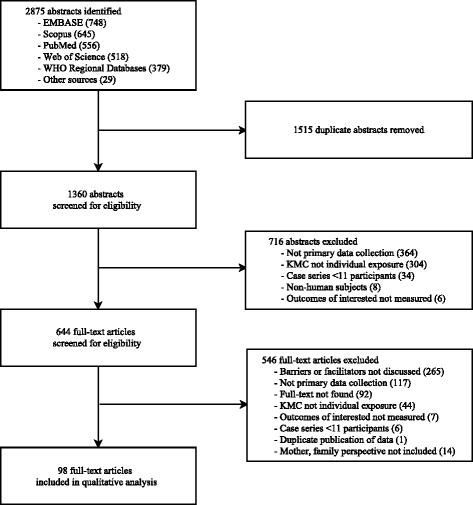

We identified a total of 2875 abstracts (748 in Embase, 645 in Scopus, 556 in Pubmed, 518 in Spider web of Science, 379 in WHO Regional Databases, and 29 from other sources). There were 1360 abstracts after removing duplicates. 716 were excluded after title and abstract review, and the full text was reviewed for 644. A total of 98 were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). All studies were considered of sufficient quality to include in the assay.

Systematic review flow chart

The bulk of publications were published within the past 5 years, had a sample size less than fifty, and recruited participants from health facilities. Ane-third of the studies were conducted in the Americas, 26.five% in Africa, 16.3% in Europe, and the remaining in Southeast Asia, Eastern Mediterranean, Western Pacific, or in multiple regions. More than half of the studies were conducted in an surface area with a neonatal bloodshed rate < 15 deaths per k live births (Tabular array 1).

After analyzing the data nerveless from the family perspective, we confirmed that caregivers are an essential component of the KMC adoption organisation as they are the primary decision-makers and are responsible for baby feeding and skin-to-pare contact. We identified 4 themes surrounding the interaction betwixt caregivers and the KMC intervention: buy in and bonding, social support, time, and medical concerns. Furthermore, we identified barriers and enablers of KMC adoption by families inside the context of the health organisation and the broader social context. These themes are summarized in Table 2.

Barriers and enablers for caregiver adoption of KMC

Caregiver buy-in and bonding

Buy-in and bonding referred to the acceptance of KMC, belief in the benefits of KMC to mothers and preterm infants, and reported perceptions of bonding between mother and baby.

Uptake of KMC was impaired by limited buy-in to KMC by mothers, fathers, and families. For case: "My experience told me this KMC was non right…so before caesarean section (in the coming together with a neonatal nurse). I was worried about it." (Father) [xi]. Mothers were less likely to accept KMC if healthcare workers could not clearly explain the benefits of KMC. Parents reported that they were simply told to perform KMC without explanation why or how to do so, and the feeling that KMC was forced upon them hindered purchase-in from caregivers [12]. Another barrier to parental buy-in occurred when caregivers perceived that their newborn did not bask KMC. In some areas due to the hot climate, parents observed their infant became irritable or "stinky" during SSC [13]. Less frequently, caregivers mentioned discomfort at not being able to see their newborn during KMC [14]. Another bulwark was lack of bonding by mothers with their preterm infants [xi]. In some cases lack of bonding with the infant was due to fearfulness, stigma, shame, guilt, or anxiety about having a preterm baby [15, 16], and some did not want to continue the baby at all [17]. For example: "I wished that I had had a miscarriage instead of delivering this preterm, information technology would exist better. I never thought that this baby would survive; I idea that information technology would die any time" (Mother) [17].

Notwithstanding, positive perceptions among mothers, fathers, and families regarding the potential benefits of the intervention promoted KMC uptake. Caregivers who successfully implemented KMC perceived that performing KMC calmed their baby [xviii–22]. These mothers observed their newborns sleeping longer during peel-to-skin contact; infants were described as less broken-hearted, more restful, more than willing to breastfeed, and happier to be in SSC position than in an incubator [eighteen, 23]. KMC was also perceived equally a healing mechanism for the parents. It helped mothers and fathers recover emotionally and physically, equally well as create a family bond [24]. KMC made mothers feel useful. For example: "Every time I hold her, the monitors-everything-did better. Her oxygen SATs did better, I actually think I helped her…and think that the human contact and…hearing my heart and everything, I actually think that helped her" [19]. Some fathers reported feeling needed and enjoyed participating in the early care of their newborn. Further, families using KMC described the time during and subsequently KMC as relaxed, calm, happy, natural, instinctive, and rubber [25–xxx]. Parents reported that the bonding associated with KMC felt continued, familiarizing, comforting, and logical. Mothers preferred KMC to traditional incubators because they felt closer to their babies, and it put them at ease [31].

Social support for caregivers

Social back up referred to the perception and reality that one has assistance from other people to perform KMC. While practicing KMC, mothers and fathers did not feel supported past their families or communities [fifteen, 25]. Mothers experienced a lack of support from healthcare workers. Some hospital staff were resistant to family unit participation in caring for the baby while in the infirmary [32]. Healthcare workers were occasionally considered to be loud and uncaring by parents [33, 34]. Additionally, KMC was impaired when parents perceived that HCWs did non respect family privacy [35]. Fathers reported lack of support from guild and frequently voiced discomfort about performing KMC because of societal norms, as many fathers felt that childcare should be the role of the female parent [fifteen, 36]. Older generations, mothers-in-police force, and grandmothers in particular, did not find KMC to exist an appropriate method to care for newborns [37].

In contrast, KMC uptake was promoted past societal credence of paternal participation in childcare, past family unit and community acceptance of KMC, and past the presence of engaged HCWs [38, 39]. In societies where gender roles were more equal, there were fewer barriers to fathers performing KMC [39, 40]. Paternal involvement played a big part in KMC uptake–either past segmentation of labor or by helping the female parent feel comfy [41]. Mothers were grateful to have someone help them during KMC, such as grandmothers and sisters, who could take care of housework and aid with the newborn. Within the maternity ward, peer support from other mothers who shared their KMC experiences also promoted credence [36, 42]. Additionally, the presence of well-trained nurses reduced maternal apprehension almost practicing KMC and handling their newborn, facilitating the implementation of KMC [43].

Caregiver time for KMC adoption

KMC guidelines recommend continuous SSC for as long as possible until the newborn reaches a certain weight (unremarkably 2000 thou), certain historic period (usually 2 weeks after nativity), or no longer tolerates it [iv]. The lengthy time needed to provide KMC was a barrier for caregivers. KMC was hard to perform at long intervals if the mother was depressed, lonely, or recently had a C-section [44]. Many mothers found KMC functioning at home to be a burden due to other responsibilities at home or work. For case, 1 mother said "Obviously I've got a married man and another child at domicile, and obviously accept to cook…you have to clean and do a lot of other things, besides looking after yourself and the baby" (Mother) [42]. Another mother noted: 'Although I am very satisfied with the KMC method, information technology made me experience divided, as I was unable to be close to my other child. This must be even more complicated for those whose infant needs a longer period of infirmary stay." (Mother) [27]. Some other difficulty was commuting between home and KMC wards [17, 18, 27, 36, 39, 42, 45, 46]. Thus, the power to practise KMC at dwelling, rather than in a facility, promoted the uptake of KMC by allowing caregivers to attend to other chores [47]. Parents (also every bit staff) noted that unlimited visitation hours enabled adoption of KMC. Furthermore, facility staff felt every bit though parents were less interfering when they were immune unhindered access to their babies [48].

Caregiver medical concerns

Medical concerns, including the clinical condition of the mother or newborn, may besides be a barrier that prevents KMC uptake. For examples, mothers in Ghana found SSC problematic because they fright that past touching the umbilical cord of the newborn it would "dissever into two," and cause pain, haemorrhage, or sickness [49]. Clinical consequences of KMC for mothers included fatigue, depression, and postpartum hurting. Some mothers experienced discomfort sleeping upright with a newborn in KMC position [13, 39]. Postpartum pain was considered a hindrance to SSC, peculiarly after a C-section [29, 39, 49, 50]. Notwithstanding, women practicing KMC idea information technology helped them to recover from postpartum depression [51]. Mothers seemed to be satisfied with the method and felt that it helped save stress [31, 52].

Health organization barriers and enablers for caregiver adoption of KMC

Adoption of KMC by caregivers mostly begins in the context of the wellness system, and caregivers may interact with any of the core components of a health system. We constitute that financing and service delivery were aspects of the wellness organization that influenced caregiver adoption of KMC.

Financing

First, in the case that the newborn remained in the hospital subsequently the female parent was discharged, lack of money for transportation and the distance to the hospital were often reported as the biggest challenges to KMC implementation; these were also barriers to returning to the health facility for follow upwardly after both female parent and babe were discharged merely continuing KMC [53–56]. In an evaluation of a Kangaroo Care inpatient ward of a 3rd hospital in Malawi, ten% mothers whose children died reported the distance to the health facility or lack of transport money equally the reason they did non get the hospital when something was wrong with their newborn; similarly, nearly forty% of mothers reported lack of transport money every bit the reason they did not go the hospital for their follow upwardly dispensary appointments [56]. In Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, poor public transportation and the difficulty of returning to the hospital after restarting work were the most frequently mentioned challenges to performing skin-to-pare contact on a daily basis while the newborn was still hospitalized [55]. On the other hand, free medical service enabled parents to stay at the clinic longer as needed. Likewise, parents in Harare, Zimbabwe believed that KMC decreased the cost of hospital bills and assumed that it was a cheaper option than conventional incubator care or a prolonged hospital stay [15].

Service delivery

For caregivers, lack of privacy and KMC resources at facilities presented obstacles to KMC adoption (Appendix). Structurally, at that place was a lack of private space for mothers to perform KMC and a lack of space for mothers to remain in the infirmary with the newborn [57, 58]. Mothers felt uncomfortable and exposed equally staff continued to come in and out during KMC [25]. For example, "There were always people around. It is harder (to exist pare to skin) when there are people other people coming in and out. Private rooms will assistance." (Mother) [50]. Another mother reported: "From seven in the morning until five in the afternoon people came in all the time. People came in to clean the room, make clean the bathroom, to cheque on me and someone else to bank check on the infant. Every xv minutes someone dissimilar would come in. I could never relax. It was exhausting. It was stressful. I couldn't relax." (Mother) [50]. Lack of resources at facilities (e.thou. chairs, beds, linens, defunction, KMC wraps, etc.) was too a barrier to adoption. At one facility materials donated for KMC were put into VIP units rather than the KMC ward [54].

However, the provision of private spaces, a quiet temper, and dedicated resources promoted the acceptance and uptake of KMC [34]. Privacy screens or private rooms immune the family separation from hospital staff and other patients and offered a quieter temper for the mothers to conduct KMC [59].

Social and cultural barriers and enablers for caregiver adoption of KMC

We hypothesized that the broad social context (e.k. demographic, economical, and cultural factors) influence caregiver adoption of KMC. For instance, surveys from 15 low-income countries noted that wellness care professionals often plant that KMC was thought of as substandard or as "the poor man's alternative" [36]. Besides, caregiver adherence to traditional newborn practices was reported every bit a barrier to KMC [55]. Traditional early bathing behavior was seen every bit having numerous benefits and was identified as an ingrained beliefs by studies conducted in Ghana and Bangladesh [17, threescore]. One traditional nascency bellboy noted: "The kid needs to exist bathed immediately in order to shape the head because whenever a kid is delivered the head is very apartment and so you need to sharpen information technology to make it round" [60]. A mother who had recently delivered noted that "Babies are normally bathed soon after birth because it will aid them feel clean and good for you" [60]. Other traditional practices, such as sleeping by a lamp and smearing the infant with oil, make uptake of KMC more hard. In reports from Republic of ghana and Republic of malaŵi, where carrying the babe on the back was common, information technology seemed foreign to place the baby on the front, equally instructed by KMC. One woman explained: "The back is stronger than the forepart and meliorate for carrying" [49]. In some contexts, it was considered unclean to have the mother behave the infant on her chest without a diaper [36]. Stigma surrounding having a preterm babe can be severe and tin can act as a bulwark to continued practice of KMC.

Dissimilar approaches to gender roles, the function of parents in childcare, the function of men in the household, and the roles of other family members also influenced KMC uptake [fifteen, 32, 36]. For instance, some fathers reported feeling uncomfortable practicing KMC in public, learning how to perform KMC while other people were present, or being scrutinized by nurses [42, 61]. Additionally, in some cases, mothers and traditional nascency attendants reported feeling uncomfortable with the male parent performing their duties [25].

Discussion

Kangaroo mother care is a circuitous intervention, as defined in our conceptual framework, because user (i.e. caregiver) appointment is high and caregiver (i.eastward. the primary 'adoption arrangement') beliefs dominates our definition of 'successful implementation' of the intervention [eight]. Thus, scale-upward of this intervention around the world relies heavily on enabling caregivers to successfully adopt KMC. We found that purchase-in and bonding, social support, time, and medical concerns were major themes defining the interaction between families and the KMC intervention. Furthermore, nosotros identified financing and service delivery as barriers (and potential enablers) of KMC adoption within the context of the health system. Additionally we identified social and cultural norms that played an important role in the adoption of KMC.

Efforts to implement and scale up KMC must work to ensure a positive experience for caregivers. For case, the benefits of KMC to the newborn and caregivers must be clearly explained to anybody involved. One approach is to ensure healthcare workers nowadays information virtually KMC in a standardized style to caregivers and extended families, with attending paid to their concerns. Additionally, testimonials about the effectiveness of KMC could exist given by caregivers who accept successfully cared for a preterm or depression birthweight baby in the by; such an arroyo is recommended in the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) KMC Guide [62]. Demonstrations and supervised practice can raise caregiver conviction. Approaches to enhance newborn-caregiver bonding are needed. For instance, programs might create a vocal about KMC to exist sung to the baby, or healthcare workers could demonstrate the change in infant temperature after a flow of skin to pare contact [63]. Despite efforts and ideas from programs and practitioners about how to create a positive KMC feel for caregivers, in that location is limited evidence well-nigh which approaches are effective.

We establish that social support can enhance the uptake and duration of KMC. To enhance social support and promote positive attitudes nigh KMC, the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) KMC Guide recommends that programs undertake sensitization to KMC at the national, health facility, and community levels. At the community-level, recommended activities include celebrations for the 'graduation' of a baby from KMC or discussions nearly KMC through radio or other public forums [62]. Similarly, a plan in Malawi asked respected grandparents to promote KMC and newborn intendance beliefs. In the Agogo (the Chitumbuka word for grandparent) Program, the Ekwenedni Church of Primal Africa Presbyterian (CCAP) Mission Infirmary trained nearly 4000 grandparents. Later, grandparents provided private and group counseling in their respective villages, using drama, song, and poems to share key letters. An evaluation of the programme ended that grandparents were successful in promoting behavior change surrounding maternal and newborn care [64]. Encouraging family unit members to provide support by assisting mothers with other household responsibilities or coaching mothers how to ask for this support may likewise increase duration of KMC later on hospital discharge. Currently, there is limited testify about the effectiveness of such sensitization efforts.

Interactions between healthcare workers and families may either encourage or discourage caregiver adoption of KMC. This is consistent with research which demonstrated that interpersonal healthcare worker behavior is a pregnant correspondent to patient satisfaction with maternal wellness services, which subsequently influences service utilization [65–67]. Healthcare workers and facilities tin can be supportive in their words and deportment, by providing privacy for the family unit equally they larn KMC and by ensuring unlimited visitation hours so that KMC can happen without time or schedule constraints. Health system concerns regarding financing travel, nutrient, lodging, etc. may exist partially alleviated by ensuring early discharge of mother and infant from the hospital (which should always exist included equally a component of KMC). Additionally, KMC programs may consider ways to reduce hospital charges or provide transportation vouchers for families of infants with longer-than-average stays. For case, some programs in Colombia maintain social funds to provide fiscal back up to families who must travel to a health facility in the period of close follow upward after the newborn is discharged from the hospital (personal advice with Nathalie Charpak, Director Fundación Canguro). Automated cash transfers using cell telephone technology, might be a method to reduce financial barriers. Transportation and time costs may also be addressed by offer abode visits by community health workers for infant follow up. Farther studies are needed to generate show regarding the feasibility and effectiveness of such an approach.

Information technology is important to acknowledge that mothers, fathers, and families are adopting KMC within a broader social context. Several studies specifically noted that there may exist stigma associated with having a preterm infant or around male person interest in child care, which present barriers to KMC uptake. Divisions of labor and infinite by gender accept been plant to be barriers to male participation in newborn care, in full general. However, as Dumbaugh et al note, inclusion of men in newborn care must be done in a way that is empowering for women [68]. To address the reluctance of fathers to appoint in childcare, fathers successfully engaging in SSC might go peer-mentors or demonstrators for other families. The intervention name "Kangaroo Mother Care" might too be changed so that it does non direct imply the beliefs is performed merely by the mother. Boosted research about how to encourage paternal involvement and reduce stigma surrounding these childcare strategies must be a part of KMC scale up in any context.

Strengths & limitations

The primary strength of this enquiry is that it draws on the rich torso of qualitative enquiry that tin help policy-makers and public wellness professionals to understand the circuitous context in which this intervention is implemented. Yet, our conclusions are limited by the existing body of evidence. There has been less research conducted in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa where KMC has the potential make the greatest impact. Furthermore, nearly one-half of the studies were conducted in urban settings with low neonatal mortality (<15 per 1000 live births). Additional research is needed in the places where KMC has the potential for the highest impact and should be geared towards understanding the needs of caregivers of preterm and low birthweight infants. Time to come research should also investigate ways to generate demand for KMC services.

Decision

We found that lack of buy-in, poor social support, lack of fourth dimension at the hospital or at home, and medical concerns well-nigh the mother or infant were barriers to caregiver adoption of KMC. Furthermore, we identified barriers and enablers of KMC adoption by families within the context of the health organisation and the broader social context. Future efforts to integrate KMC into local, regional, or national health systems must make efforts to identify and reduce barriers and promote enablers for successful caregiver adoption of KMC. Ultimately, KMC programs must ensure that the KMC experience is a valuable and positive experience from the caregiver perspective.

Abbreviations

- KMC:

-

Kangaroo mother care

- SSC:

-

Pare-to-peel contact

References

-

Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, Mooney MD, Levitz CE, Schumacher AE, Apfel H, Iannarone M, Phillips B, Lofgren KT, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, babe, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic assay for the Global Burden of Disease Report 2013. Lancet. 2014;384(9947):957–79.

-

Bhutta ZA, Black RE. Global maternal, newborn, and child health—and then near and yet so far. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2226–35.

-

World Health System DoRHaR. Kangaroo female parent care: a practical guide. In: WHO Library. Geneva: Earth Health Arrangement; 2003.

-

Chan GJ, Valsangkar B, Kajeepeta Due south, Boundy EO, Wall South. What is kangaroo mother care? A systematic review of the literature. J Glob Health. 2016. In press.

-

Boundy EO, Dastjerdi R, Spiegelman D, Fawzi WW, Missmer SA, Lieberman E, Kajeepeta Southward, Wall S, Chan GJ. Kangaroo Mother Care and Neonatal Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(1):1–16.

-

WHO. WHO recommendations on interventions to improve preterm nascency outcomes. In. Geneva: World Health Organization. (2015).

-

Chan GJ, Labar AS, Wall Southward, Atun R. Kangaroo mother care: a systematic review of barriers and enablers. Balderdash World Health Organ. 2016;94(2):130–41J.

-

Atun R, de Jongh T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O. Integration of targeted wellness interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(2):104–eleven.

-

Kuper A, Lingard L, Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337:a1035.

-

Kastner M, Antony J, Soobiah C, Straus SE, Tricco AC. Conceptual recommendations for selecting the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to answer research questions related to complex evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:43–ix.

-

Lemmen DF, Fristedt P, Lundqvist A. Kangaroo care in a neonatal context: Parents' experiences of information and communication of Nurse-Parents. Open Nurs J. 2013;7:41–8.

-

Martins AJVS, Santos IMM. Living in the other side of kangaroo method: the mother's experience. Rev Eletr Enf 10.3. 2008.

-

Quasem I, Sloan NL, Chowdhury A, Ahmed S, Winikoff B, Chowdhury AM. Adaptation of kangaroo mother care for community-based application. J Perinatol. 2003;23(8):646–51.

-

Brimdyr G, Widstrom AM, Cadwell Grand, Svensson K, Turner-Maffei C. A Realistic Evaluation of Two Training Programs on Implementing Skin-to-Skin as a Standard of Intendance. J Perinat Educ. 2012;21(3):149–57.

-

Kambarami RA, Mutambirwa J, Maramba PP. Caregivers' perceptions and experiences of 'kangaroo intendance' in a developing country. Trop Dr. 2002;32(3):131–three.

-

Duarte ED, Sena RR. Kangaroo mother intendance: feel report. Revista Mineira de Enfermagem. 2001;5(1):86–92.

-

Waiswa P, Nyanzi Southward, Namusoko-Kalungi S, Peterson S, Tomson Grand, Pariyo GW. 'I never idea that this infant would survive; I thought that it would dice any fourth dimension': perceptions and care for preterm babies in eastern Republic of uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(x):1140–7.

-

Dalbye R, Calais E, Berg M. Mothers' experiences of skin-to-skin care of salubrious full-term newborns–A phenomenology study. Sex activity Reprod Healthc. 2011;2(3):107–11.

-

Neu Grand. Parents' perception of pare-to-skin intendance with their preterm infants requiring assisted ventilation. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1999;28(2):157–64.

-

Crenshaw JT, Cadwell K, Brimdyr K, Widstrom AM, Svensson K, Champion JD, Gilder RE, Winslow EH. Use of a video-ethnographic intervention (PRECESS Immersion Method) to improve pare-to-peel care and breastfeeding rates. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7(2):69–78.

-

Keshavarz Grand, Haghighi NB. Effects of kangaroo contact on some physiological parameters in term neonates and hurting score in mothers with cesarean section. Koomesh. 2010;11(2):91–9.

-

Johnston CC, Campbell-Yeo Chiliad, Filion F. Paternal vs maternal kangaroo intendance for procedural hurting in preterm neonates: a randomized crossover trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(nine):792–6.

-

Ludington-Hoe SM, Johnson MW, Morgan One thousand, Lewis T, Gutman J, Wilson PD, Scher MS. Neurophysiologic assessment of neonatal slumber organisation: Preliminary results of a randomized, controlled trial of skin contact with preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):E909–23.

-

Tessier R, Cristo MB, Velez South, Giron M, Nadeau L, Figueroa de Calume Z, Ruiz-Palaez JG, Charpak North. Kangaroo Mother Care: A method for protecting loftier-risk low-birth-weight and premature infants against developmental filibuster. Infant Behav Dev. 2003;26(3):384–97.

-

Sá FE, Sá RC, Pinheiro LMF, Callou FEO. Interpersonal relationships betwixt professionals and mothers of premature from Kangaroo-Unit. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde. 2010;23(ii):144–9.

-

Roller CG. Getting to know you: mothers' experiences of kangaroo care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34(2):210–7.

-

Blomqvist YT, Nyqvist KH. Swedish mothers' experience of continuous Kangaroo Mother Intendance. J Clin Nurs. 2011;twenty(9–ten):1472–80.

-

Heinemann AB, Hellstrom-Westas L, Hedberg Nyqvist 1000. Factors affecting parents' presence with their extremely preterm infants in a neonatal intensive intendance room. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(vii):695–702.

-

Darmstadt GL, Kumar 5, Yadav R, Singh Five, Singh P, Mohanty S, Baqui AH, Bharti N, Gupta S, Misra RP, et al. Introduction of community-based skin-to-pare care in rural Uttar Pradesh, India. J Perinatol. 2006;26(10):597–604.

-

Nyqvist KH, Kylberg Eastward. Application of the baby friendly hospital initiative to neonatal care: suggestions by Swedish mothers of very preterm infants. J Hum Lact. 2008;24(3):252–62.

-

Legault K, Goulet C. Comparison of kangaroo and traditional methods of removing preterm infants from incubators. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 1995;24:501–6.

-

Colameo AJ, Rea MF. Kangaroo Female parent Care in public hospitals in the Land of Sao Paulo, Brazil: an analysis of the implementation process. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22(3):597–607.

-

Blomqvist YTF, Frölund L, Rubertsson C, Nyqvist KH. Provision of Kangaroo Mother Care: Supportive factors and barriers perceived by parents. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27:345–53.

-

Heinemann AB, Hellstrom-Westas 50, Nyqvist KH. Factors affecting parents' presence with their extremely preterm infants in a neonatal intensive care room. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:695–702.

-

Neu Thou. Kangaroo care: is it for anybody? Neonatal Netw. 2004;23(5):47–54.

-

Charpak Due north, Ruiz-Pelaez JG. Resistance to implementing Kangaroo Mother Care in developing countries, and proposed solutions. Acta Paediatr. 2006;95(5):529–34.

-

Kambarami R. Kangaroo care and multiple births. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2002;22(1):107–8.

-

Kambarami RA, Chidede O, Pereira N. Long-term outcome of preterm infants discharged home on kangaroo care in a developing land. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2003;23(1):55–9.

-

Blomqvist YT, Frölund L, Rubertsson C, Nyqvist KH. Provision of Kangaroo Mother Intendance: Supportive factors and barriers perceived by parents. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27:345–53.

-

Calais E, Dalbye R, Nyqvist K, Berg M. Peel-to-pare contact of fullterm infants: an explorative study of promoting and hindering factors in two Nordic childbirth settings. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(vii):1080–xc.

-

Moreira JO, Romagnoli RC, Dias DAS, Moreira CB. Kangaroo mother programme and the human relationship mother-baby: qualitative research in a public maternity of Betim city. Psicol estud. 2009;fourteen(3):475–83.

-

Leonard A, Mayers P. Parents' Lived Experience of Providing Kangaroo Care to their Preterm Infants. Health SA Gesondheid. 2008;xiii(4):16–28.

-

Solomons N, Rosant C. Noesis and attitudes of nursing staff and mothers towards kangaroo mother intendance in the eastern sub-district of Cape Town. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2012;25(1):33–9.

-

Kymre IG, Bondas T. Balancing preterm infants' developmental needs with parents' readiness for skin-to-skin care: A phenomenological written report. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2013;8(1):21370.

-

Toma TS, Venâncio SI, Andretto DA. Percepção das mães sobre o cuidado do bebê de baixo peso antes e após implantação do Método Mãe-Canguru em hospital público da cidade de São Paulo, Brasil. [Maternal perception of low nascence weight babies before and following the implementation of the Kangaroo Mother Care in a public hospital, in the urban center of São Paulo, Brazil]. Rev Bras Saúde Matern Baby. 2007;vii(3):297–307.

-

Castiblanco López North, Muñoz de Rodríguez L. Vision of mothers in care of premature babies at home. Av enferm. 2011;29(1):120–9.

-

Ibe OE, Austin T, Sullivan K, Fabanwo O, Disu E, Costello AM. A comparison of kangaroo mother intendance and conventional incubator care for thermal regulation of infants < 2000 k in Nigeria using continuous ambulatory temperature monitoring. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2004;24(iii):245–51.

-

De Vonderweid U, Forleo Five, Petrina D, Sanesi C, Fertz C, Leonessa ML, Cuttini M. Neonatal developmental intendance in Italian Neonatal Intensive Care Units. Ital J Pediatr. 2003;29(3):199–205.

-

Bazzano A, Hill Z, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Manu A, ten Asbroek G, Kirkwood B. Introducing habitation based skin-to-pare intendance for low birth weight newborns: a pilot approach to instruction and counseling in Ghana. Glob Health Promot. 2012;19(3):42–9.

-

Ferrarello DH, Hatfield L. Barriers to skin-to-skin care during the postpartum stay. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2014;39:56–61.

-

Silva MBO, Brito RCS. Perceptions and neonatal intendance behavior of women in a Kangaroo-female parent Care Program. Interao Psicol. 2008;12(2):255–66.

-

Furlan CEFB, Scochi CGS, Furtado MCC. Percepção dos pais sobre a vivência no método mãe-canguru. Perception of parents in experiencing the kangaroo female parent method. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2003;eleven(4):444–52.

-

Bergh AM, et al. Retrospective evaluation of kangaroo mother intendance practices in Malawian hospitals. Healthy Newborn Network. 2007.

-

Bergh AM, Sylla M, Traore IMA, Diall Bengaly H, Kante K, Diaby Kaba Northward. Evaluation of kangaroo mother care services in Republic of mali. 2012.

-

Boo NY, Jamli FM. Brusk duration of skin-to-skin contact: Effects on growth and breastfeeding. J Paediatr Child Wellness. 2007;43(12):831–6.

-

Blencowe H, Kerac M, Molyneux E. Safe, effectiveness and barriers to follow-upward using an 'early discharge' Kangaroo Intendance policy in a resource poor setting. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55(4):244–8.

-

Bergh AM, Davy K, Otai CD, Nalongo AK, Sengendo NH, Aliganyira P. Evaluation of kangaroo female parent care services in Uganda. 2012.

-

Bergh AM, Banda L, Lipato T, Ngwira G, Luhanga R, Ligowe R. Evaluation of kangaroo mother intendance services in Malawi. 2012.

-

Johnson AN. Factors influencing implementation of kangaroo holding in a Special Intendance Plant nursery. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(i):25–ix.

-

Colina Z, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Manu A, Okyere Due east, Kirkwood BR. Keeping newborns warm: behavior, practices and potential for behaviour change in rural Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;fifteen(x):1118–24.

-

Eleutério FRR, Rolim KMC, Campos ACS, Frota MA, Oliveira MMC. The imaginary of mothers near experiencing the mother-kangaroo method. Cinc Cuid Saude. 2008;vii(4):439–46.

-

MCHIP. Kangaroo Mother Intendance: Implementation Guide. The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) of USAID. 2012.

-

Kumar Five, Mohanty S, Kumar A, Misra RP, Santosham M, Awasthi S, Baqui AH, Singh P, Singh V, Ahuja RC, et al. Effect of customs-based behaviour alter direction on neonatal mortality in Shivgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9644):1151–62.

-

Zyl MV. The Ekwendeni Agogo Approach: Grandparents as agents of alter for newborn survival. Salubrious Newborn Network. 2010.

-

Kujawski S, Mbaruku Thousand, Freedman LP, Ramsey K, Moyo Westward, Kruk ME. Clan Between Disrespect and Abuse During Childbirth and Women's Conviction in Health Facilities in Tanzania. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(10):2243–l.

-

Avortri GS, Beke A, Abekah-Nkrumah G. Predictors of satisfaction with child nascence services in public hospitals in Republic of ghana. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2011;24(three):223–37.

-

Larson Due east, Hermosilla S, Kimweri A, Mbaruku GM, Kruk ME. Determinants of perceived quality of obstetric care in rural Tanzania: a cross-sectional report. BMC Wellness Serv Res. 2014;14:483.

-

Dumbaugh M, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Manu A, x Asbroek GH, Kirkwood B, Hill Z. Perceptions of, attitudes towards and barriers to male interest in newborn care in rural Ghana, West Africa: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:269.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ellen Boundy, Roya Dastjerdi, Sandhya Kajeepeta, Stacie Constantian, and Amy Labar for reviewing and abstracting the information, and Rodrigo Kuromoto and Eduardo Toledo for reviewing non-English manufactures. We acknowledge Kate Lobner for developing and running the search strategy.

Funding

This publication was supported by Save the Children's Saving Newborn Lives program.

Availability of information and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

GC conceptualized and designed the review. IB, SC reviewed and abstracted data. ES, GC drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and canonical the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicative.

Ideals approving and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding writer

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite appropriate credit to the original author(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/null/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Well-nigh this article

Cite this article

Smith, East.R., Bergelson, I., Constantian, Due south. et al. Barriers and enablers of health organisation adoption of kangaroo female parent care: a systematic review of caregiver perspectives. BMC Pediatr 17, 35 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12887-016-0769-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/x.1186/s12887-016-0769-v

Keywords

- Kangaroo mother intendance

- Skin to skin care

- Health organization integration

- Mother

- Father

- Family

- Caregiver

birminghamstruity.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-016-0769-5

0 Response to "A Nurse Is Providing Education About Family Bonding to Parents Who Recently Adopted a Newborn"

Post a Comment